Momentum

When it comes to collisions, while we are taught to believe speed is the sworn enemy of docks and other boats, actually it is momentum rather than speed that the docks should be shivering in the pilings. Imagine both a fly and a boat hitting a dock at 10 knots. The fly hitting is a buzz kill while the boat will end up on youtube.

What is Momentum?

Momentum, in a boat context, refers to the propensity of a boat to want to continue moving. Momentum is the multiplication product of the boat’s mass and its velocity (speed). The formula for momentum (p) is:

p = m × v

where:

p represents momentum,

m is the mass of the boat,

v is the velocity of the boat.

(and don’t worry – we’re not testing you on this formula, but it’s helpful to understand!)

The bigger that p becomes from the formula – either v or m (or both), the bigger the damage. You typically don’t control the mass m of the boat (except for supplies and people but that is small. However, you certainly control the velocity (v) of the boat by managing the boat’s speed through gear and throttle controls.

Remember in high school when we learned Newton’s First Law of Motion?Refresher: an object at rest wants to stay at rest and an object in motion wants to stay in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force. Here is an example of Newton’s law and momentum in boating: the mass of a typical 30 ft boat is about 8,000 to 10,000 pounds of ‘displacement’ (3500 – 4500 kg). When docking by Newton’s First Law of Motion and using the momentum formula: that’s about 4000 kg of boat mass m in motion v at say 5 knots that creates 10,000 kg.m/s of p which needs to go to zero to prevent damage. That is, the boat REALLY DOESN’T WANT TO STOP (i.e., Newton) without an unbalanced force – which is either hitting the dock, shore, another boat, or using your engine to bleed off the velocity!!! While displacing the water out of the way does help slow the boat down it takes a fair distance to do this. Not much extra math is required to figure out this practical lesson, you either hit something or use your engine to slow the boat to a stop. The trick is to understand at what rate your boat slows down. This you have to learn by getting the feel of your boat and then be able to eventually judge from your current speed how far out from the dock you need to be taking the right actions to stop perfectly at the dock. The lesson is that boats often have more mass than most people realize, and so momentum becomes a key factor when maneuvering. Preferably, we use our engines and maneuver appropriately, and when in doubt take it slow (thus the saying “Slow is Pro”)! |

Other factors affecting your momentum

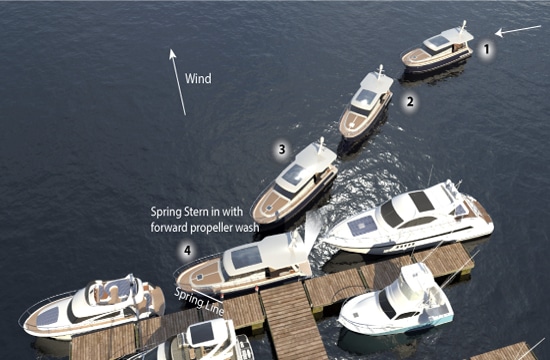

- Wind and current: going against or with the wind and current certainly affects your ability to change your momentum. For example, an unfriendly current can drag you at high speed into the dock – or against a protruding and tilted outboard engine and its hungry propeller.

- Hull Design: Pull the throttle to neutral and you’ll find some boats slow down faster than others. This is the drag of water acting on the hull. It assists in bleeding off momentum but hinders picking up speed.

The Role of Momentum when Maneuvering Under Power

- Inertia, Momentum, and Engine Power: The inertia of an object is its resistance to changes in motion, and is directly related to its mass. While a boat at rest has no momentum it has a lot of inertia – you have to apply force to get it to move. When using the engine, a boat with greater inertia will require more power to start moving and more time and distance to stop.

- Acceleration and Deceleration: Engine power allows for controlled acceleration and deceleration. Smooth throttle adjustments are key to managing the boat’s momentum.

- Steering and Direction Changes: The boat’s inertia affects how it responds to steering inputs (change in directional motion). The heavier the boat, the more force it takes to change its direction or speed. It is thus imperative to learn how to operate each size and type of boat. They are all different and have different inertia.

Best Practices for Managing Momentum:

- Regular Practice: Spend time practicing maneuvers with the engine to become familiar with how your boat responds to throttle inputs. Practice docking, turning, and stopping in various conditions to build confidence and skill.

- Smooth Throttle Use: Always use the throttle smoothly to avoid sudden changes in momentum.

- Plan Ahead: Anticipate your next move and start adjusting the throttle well in advance. Whether you’re docking, stopping, or making a turn, planning ahead allows you to manage the boat’s momentum more effectively.

- Communication with Crew: Ensure clear and concise communication with your crew about your intentions and upcoming maneuvers. This coordination is especially important when managing the boat’s momentum during complex maneuvering.

There is Stopping and There is STOPPING

Pulling up to a mooring ball with a bow person trying to hook the mooring ball pendant is an example of needing to stop dead in the water. This is different to pulling the throttle back to neutral and stopping the engine – in this case your boat is still moving through the water from its momentum. Stopping dead in the water and stopping the engine is an important distinction.

|

Anecdote: While sitting on a mooring ball in Hope Town, The Bahamas (well not actually sitting on it – that would be hard – while sitting on a boat moored to a mooring ball) and having a nice lunch we were presented with some entertainment. And maybe entertainment is a bad use of a word because the scenario that unfolded was to the detriment of the operators. A couple came in on their sailboat to pick up a mooring ball. The wife was on the bow ready with a boat hook and the husband was steering the boat. As they got closer to the mooring ball we all observed that (1) they were coming in from an upwind position (which would hinder their ability to slow down) and (2) that they were coming in pretty hot (fast (= lots of momentum)). Sure enough, the wife expertly hooked the mooring ball pendant while the husband threw the gear into reverse. The boat did not stop and quickly ripped the boat hook out of the wife’s hand. Then to our amazement, the boat stopped instantly with a jerk of the bow dipping down. Huh? What had happened was that the mooring ball pendant had gotten caught in the fast reverse spinning prop which abruptly brought the boat to a dead stop in the water. We all announced that that is one way of picking up a mooring. Of course, it takes a little more to get off and probably a few $ to the harbor master to fix the mooring and the diver to untangle the mess – and possibly to the mechanic to fix the prop shaft et al. Still – it is one way of doing it! I’m sure that in hindsight the husband learned the difference between stopping the engine and stopping dead in the water. Hint approach from downwind – slowly – and know the difference between stopping and STOPPING. |

To determine if you are stopped dead in the water, take a look over the side of your boat and look at the ripples in the water. This gives you an indication of your relative speed to the water. If there is current take that into account. Knowing that your boat is stopped dead in the water gives your bow crew time to pick up a mooring ball pendant and other activities such as anchoring. At times your bow crew may hand signal to you to back away or to move up – knowing your relative movement to the water is the only way to make such precise movements. Look over the side!